Rewriting the Symfony Demo with MongoDB

In this post, I’ll walk through rewriting parts of the Symfony Demo application to use MongoDB instead of MySQL. We’ll explore document design, embedded vs referenced data, search capabilities, and the trade-offs that come with a document database.

Setup

I started by creating a new Symfony Demo project, and installing the doctrine/mongodb-odm-bundle.

The Data

Let’s start with the data we want to store, and how it relates to each other.

The objects we want to store in the demo app are the following:

- Posts

- Tags

- Comments

- Users

How does this all relate?

- A post can have many tags, a tag can have many posts

- A post has one user (the author). A user can have many posts

- A post has many comments

- A comment has one author

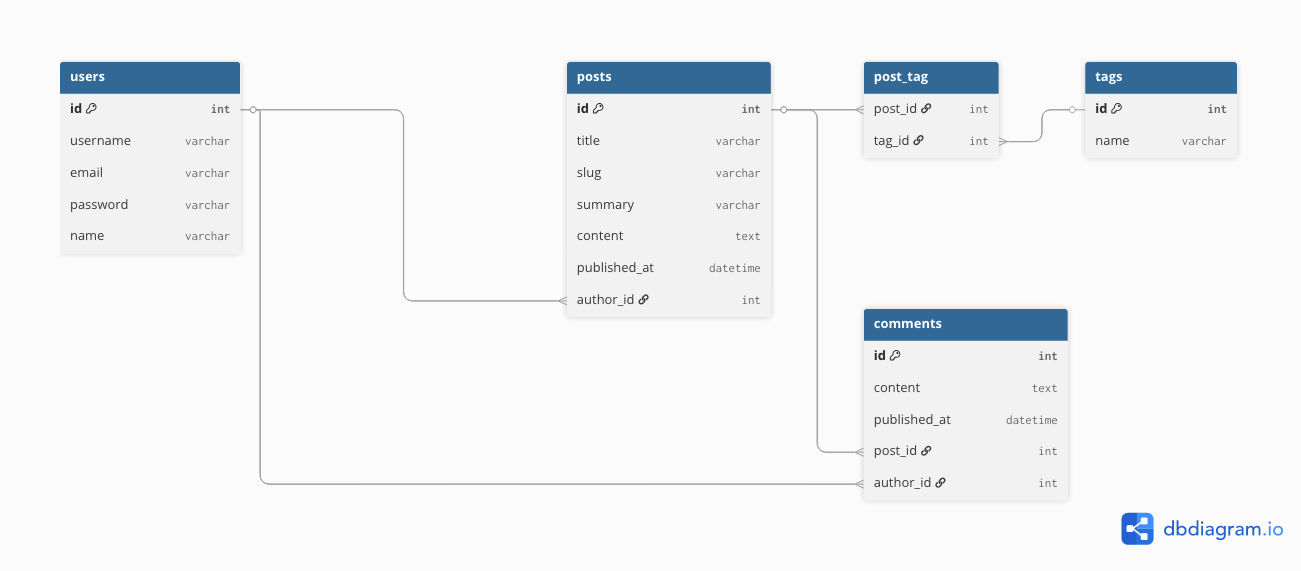

The Existing (Relational) Schema

In our relational db, we basically just structure the data the way we listed it above. Each object gets its own table. And with relations (OTO, OTM, MTM), we make the links between the data.

As we know, in SQL, our data is stored in tables. For example, a simple schema can look like this:

Designing our MongoDB Schema

When designing our MongoDB documents, we not only think about the data and how it relates, but also how this data will be used. For the demo, we can think of the following use cases:

- Overview page: shows a snapshot of the post, including some basic author info, and the tags relating to the posts

- Search: shows the same post snapshot as the overview page does

- Tag search page: also shows the same post snapshot

- Post detail page: shows the post, post tags, author name, but also comments and their author names

We can make some conclusions from this list of info:

- A post is always shown together with:

- author name

- tags

- A comment is always shown together with:

- author name

- A comment is never shown without its post

Based on this, we can start designing our documents.

The main difference in MongoDB is that our entities, or documents, are JSON structures. So, let’s make a basic document model of our post:

{

"_id": "ObjectId(...)",

"title": "My Post",

"slug": "my-post",

"summary": "...",

"content": "...",

"publishedAt": "2023-01-01T00:00:00.000Z"

}

As we can see, it’s just JSON as we know it.

Now, let’s think about our tags. The tags are almost never used outside the context of a blog post. (Showing tags related to a blog post is by far its main use case). There’s no real need for this to be a separate table. We can just add them as an array of strings to our Post document:

{

"...post fields...",

"tags": [

"symfony",

"mongodb",

"php"

]

}

Now let’s have a look at the author of a post. This is a user in our current relational database. So let’s make a document for this user:

{

"_id": "ObjectId(...)",

"username": "john.doe",

"email": "[email protected]",

"password": "topsecrethash",

"name": "John Doe",

"roles": ["ROLE_USER", "ROLE_ADMIN"]

}

Cool! Pretty simple document. But now, we need the relation between our post and our user (author), right? Well, sort of. Since we’re not really working with a relational database, we don’t have to work with a full relation.

This is a perfect use case for Embedded Documents. In the case of the Author, our embed will be a subset of user. As the name suggests, this means we just embed a subset of the details the user has. No need for the post to know about the roles or the email address of a user.

{

"...post fields...",

"author": {

"_id": "ObjectId(...)",

"name": "John Doe"

}

}

This brings us a cool benefit! Can you spot it?

Performance! We no longer have to join our posts to their authors! If we fetch a post from our database, we will automatically know the name of the author! We are still saving the ID as well, because you still want a reference to the original user (this will come back later).

Finally, there is one object left: the comments.

We ask ourselves the same question: do we really need to store comments in their own table? Are we ever fetching comments without the post they relate to? Usually not. So, we will store these as an array of embedded documents:

{

"...post fields...",

"comments": [

{

"_id": "ObjectId(...)",

"content": "Great post!",

"publishedAt": "2025-01-15T12:00:00Z",

"author": {

"_id": "ObjectId(...)",

"name": "Jane Smith"

}

}

]

}

Note: if we expect a large number of comments, we could also consider using a separate collection for comments, and for example only storing the last 5 comments on the post. This is to ensure the size of the Post document remains manageable. However, for this demo, we’ll keep comments embedded for simplicity.

Here you can see that, even though comments are never stored on their own, they still get a unique ID. We will also need this later.

Now that we have the structure of our object, we can start defining collections. Basically, it’s a collection of documents.

So, pretty simple in our case:

- users (a collection of User)

- posts (a collection of Post)

Bringing our final structure to the following:

users (collection)

└── User document

posts (collection)

└── Post document

├── author (embedded Author)

├── tags (string array)

└── comments (embedded array)

└── Comment

└── author (embedded Author)

PHP Implementation (Doctrine ODM)

Here’s how these documents translate to Doctrine ODM:

User Document:

#[ODM\Document(collection: 'users')]

class User

{

#[ODM\Id]

private ?string $id = null;

#[ODM\Field]

private ?string $fullName = null;

#[ODM\Field]

#[ODM\Index(unique: true)]

private ?string $username = null;

#[ODM\Field]

#[ODM\Index(unique: true)]

private ?string $email = null;

#[ODM\Field]

private ?string $password = null;

#[ODM\Field(type: 'collection')]

private array $roles = ['ROLE_USER'];

}

Embedded Author (subset of User):

#[ODM\EmbeddedDocument]

class Author

{

#[ODM\Field]

private ?string $id = null;

#[ODM\Field]

private ?string $name = null;

public static function fromUser(User $user): self

{

$author = new self();

$author->id = $user->getId();

$author->name = $user->getFullName();

return $author;

}

}

Comment (Embedded Document):

#[ODM\EmbeddedDocument]

class Comment

{

#[ODM\Id]

private ?string $id = null;

#[ODM\Field]

private ?string $content = null;

#[ODM\Field(type: 'date_immutable')]

private DateTimeImmutable $publishedAt;

#[ODM\EmbedOne(targetDocument: Author::class)]

private ?Author $author = null;

}

Post Document:

#[ODM\Document(collection: 'posts')]

#[ODM\Index(keys: ['title' => 'text', 'content' => 'text'], options: ['weights' => ['title' => 10, 'content' => 1]])]

class Post

{

#[ODM\Id]

private ?string $id = null;

#[ODM\Field]

private ?string $title = null;

#[ODM\Field]

#[ODM\Index(unique: true)]

private ?string $slug = null;

#[ODM\Field]

private ?string $summary = null;

#[ODM\Field]

private ?string $content = null;

#[ODM\Field(type: 'date_immutable')]

private DateTimeImmutable $publishedAt;

#[ODM\EmbedOne(targetDocument: Author::class)]

private ?Author $author = null;

#[ODM\EmbedMany(targetDocument: Comment::class)]

private array $comments = [];

#[ODM\Field(type: 'collection')]

private array $tags = [];

}

Notice how similar this feels to Doctrine ORM — just different attributes (#[ODM\Document] instead of #[ORM\Entity], #[ODM\EmbedOne] instead of #[ORM\ManyToOne], etc.).

Oof. If you made it this far, here’s a cookie 🍪.

Creating Our Data

I’m not gonna spend too much time here. Basically I just created a new MongoFixtures class, that does the same as the existing AppFixtures but for our MongoDB documents.

Using Our New Data!

Now that we have everything in MongoDB, we can recreate the existing pages, but with our new data!

Since I don’t plan on rebuilding the entire app including auth etc, I’m just creating pages next to the existing ones. E.g., we will add /mongo/blog next to /blog. That also allows us to easily compare.

Overview Page

Let’s start with the overview page.

On this page, we need the 10 most recent posts, with their tags and author info. And… what do you know! We have all this data in our post document! So a single query, and boom! We already have what we need to display everything!

Remember, in the MySQL implementation, this page did 3 queries, where each query also did 3 joins. On the scale of this data, that’s obviously no problem. But once the data grows, that can become an issue.

PHP (Doctrine ODM):

$qb = $this->createQueryBuilder()

->field('publishedAt')->lte(new DateTimeImmutable())

->sort('publishedAt', 'DESC')

->limit(10);

Raw MongoDB:

db.posts.find(

{ publishedAt: { $lte: ISODate() } }

).sort({ publishedAt: -1 }).limit(10)

Now of course, in our code, we don’t use this query directly. We add the paginator in between, to add some functionality. But this gives you an idea of how the query looks. This simple query gives us all the data we need for the overview page!

Searching

We can add a search index to our document. This search index allows a bit more advanced search compared to the LIKE query in SQL. It supports weighted results. So in our example, we can say a match in the title is worth more than a match in the content.

It also comes with its own downsides though.

The fancy search index doesn’t support… partial queries. For example, sym will not match a post containing symfony. So unfortunately for our specific use case, that’s not really helpful.

Therefore, we will have to do the MongoDB equivalent of the SQL LIKE. In MongoDB, that’s a regex search.

Text Search (with scoring)

Even though we’re not using it, I still wanted to show it.

Basically in our index, we will have 2 fields: title and content. And we will give them a weight of 10 and 1 respectively.

This means that a match in the title will be worth 10 times more than a match in the content. And we can use this to sort our results.

// Index on the entity

#[ODM\Index(keys: ['title' => 'text', 'content' => 'text'], options: ['weights' => ['title' => 10, 'content' => 1]])]

// ODM

$this->createQueryBuilder()

->text($query)

->selectMeta('score', 'textScore')

->sortMeta('score', 'textScore')

->limit($limit);

// Raw MQL

db.posts.find(

{ $text: { $search: "test" } },

{ score: { $meta: "textScore" } }

).sort({ score: { $meta: "textScore" } }).limit(10)

Note: The text index shown here is MongoDB’s built-in “legacy” text search. If you’re using MongoDB Atlas, you have access to Atlas Search — a fully integrated Lucene-based search service with fuzzy matching, autocomplete, and more advanced features. For a production app, that’s worth exploring. But this is not something we will be covering in this demo.

Regex Search (for partial matching)

The regex search works a bit simpler than the text search. It’s basically a regular expression that matches the query.

// ODM

$this->createQueryBuilder()

->field('title')->equals(new MongoDB\BSON\Regex($query, 'i'))

->sort('publishedAt', 'DESC')

->limit($limit);

// Raw MQL

db.posts.find({ title: { $regex: "test", $options: "i" } })

Getting All Tags

Finally, something I didn’t implement in the demo, but did want to show.

When the admin creates a new post, there is a tags field. This is an autocomplete field, that shows the existing tags if you start typing. If you type something new, it creates it.

For this, we obviously need to be able to query all our tags.

Since we didn’t make a separate collection for our tags, we will have to query it from the Posts collection. Depending on what we want, we have 2 ways of doing this.

Distinct

db.posts.distinct("tags")

I think the first option speaks for itself. Using the distinct query, we can ask MongoDB: give me all the distinct values of this field (tags) across my collection. In our case, this would be enough for the autocomplete.

Aggregate / Pipeline

Obviously, I wanted to show the 2nd option too. In our case, we don’t quite need it. But it’s very interesting to show anyways. The second option is using an aggregate. As per the docs: An aggregate calculates values for the data in a collection. So basically, aggregate just means combine many things into a summary. Cool! Let’s check out how we can do that.

Creating one is pretty simple in MongoDB, as it turns out: db.posts.aggregate(...). But, what goes between the parentheses? A pipeline!

A pipeline is basically what it says in the name. It takes some data in, passes it through various steps in the pipeline, and gives an output. For example: [Documents] → [Stage 1] → [Stage 2] → [Stage 3] → [Results].

Let’s say we want to list all tags, the number of posts using them, and the number of comments on those posts. So basically, some analytics.

We can do that with the following pipeline:

db.posts.aggregate([

{ $unwind: "$tags" },

{ $group: {

_id: "$tags",

posts: { $sum: 1 },

comments: { $sum: { $size: "$comments" } }

}},

{ $sort: { posts: -1 } }

])

Let’s break it down step by step.

Starting data:

[

{ "title": "Post A", "tags": ["php", "symfony"], "comments": [{"..."}, {"..."}] },

{ "title": "Post B", "tags": ["php", "mongodb"], "comments": [{"..."}] },

{ "title": "Post C", "tags": ["symfony"], "comments": [] }

]

Stage 1: $unwind: "$tags"

This explodes the documents into multiple documents, so each has one tag. We can see we now have duplicates in our data, but each with a unique tag:

[

{ "title": "Post A", "tags": "php", "comments": [{"..."}, {"..."}] },

{ "title": "Post A", "tags": "symfony", "comments": [{"..."}, {"..."}] },

{ "title": "Post B", "tags": "php", "comments": [{"..."}] },

{ "title": "Post B", "tags": "mongodb", "comments": [{"..."}] },

{ "title": "Post C", "tags": "symfony", "comments": [] }

]

Stage 2: $group

Here, we have multiple things happening:

_id: "$tags": Group everything by the value of the tagposts: { $sum: 1 }: Count 1 for each document (so count how many docs)comments: { $sum: { $size: "$comments" } }: Count the size of the comments of each document (so total comments on the docs with this tag, as we are still grouped by the tag)

[

{ "_id": "php", "posts": 2, "comments": 3 },

{ "_id": "symfony", "posts": 2, "comments": 2 },

{ "_id": "mongodb", "posts": 1, "comments": 1 }

]

Stage 3: $sort: { posts: -1 }

Pretty simple stage. Order by the posts field that we just added (the count of docs), and order it descending (-1):

[

{ "_id": "php", "posts": 2, "comments": 3 },

{ "_id": "symfony", "posts": 2, "comments": 2 },

{ "_id": "mongodb", "posts": 1, "comments": 1 }

]

And that’s it! Our pipeline in the aggregate now shows some basic statistics of the tags in our blog!

Updating Our Data

Of course, our document structure is pretty neat when it comes to fetching data. But what about updating data?

Let’s use 2 cases as examples.

Updating a Single Comment

Imagine a user updates their comment. This comment is stored within an array within the Post document, remember?

Let’s compare the way we do this in SQL and in MongoDB.

SQL:

UPDATE comments SET content = 'Updated!' WHERE id = 123

Since comments is its own table, this is probably the easiest update query ever.

MongoDB:

db.posts.updateOne(

{ "comments._id": ObjectId("...") },

{ $set: { "comments.$.content": "Updated!" } }

)

There is a bit more happening here. Since comments are embedded within posts, we’re actually doing an update query on the posts collection.

The updateOne structure looks like this: updateOne(filter, update, options)

- The filter says: find the post that contains the comment with the specified ID

- And then we call

$setoncomments.$. The$is the positional operator, and means “the first element that matched”. So in this case,comments.$is the comment that matched the filter, since there is only one with that specific ID.

Updating a Username

This is where things get a bit more complex. Remember how we said it was a good idea to embed this basic author data in a post, so we wouldn’t have to do joins? And same for the comments? Well… that now means, if a user changes their username, we have to update all posts and all comments from that user.

This is of course a design decision. The reason we embedded this is because a username is not likely to change, if at all. But, nonetheless, what if you have to update embedded data?

Let’s say our John Doe user changes their name. There are multiple places where we need to update this:

users collection: { _id: "user1", name: "John Doe" }

posts collection:

└── Post 1: { author: { _id: "user1", name: "John Doe" } }

└── Post 2: { author: { _id: "user1", name: "John Doe" } }

└── Post 3:

└── comments[0]: { author: { _id: "user1", name: "John Doe" } }

└── comments[1]: { author: { _id: "user1", name: "John Doe" } }

We have to run multiple MongoDB queries to update the data:

1. Update the user (source of truth):

db.users.updateOne(

{ _id: ObjectId("user1") },

{ $set: { name: "Johnny Doe" } }

)

This is the easy one. We update the user that matched the ID. It’s basically a simple UPDATE statement as we know it.

2. Update posts they authored:

db.posts.updateMany(

{ "author._id": ObjectId("user1") },

{ $set: { "author.name": "Johnny Doe" } }

)

This one reminds us of the update we did on comments, except we use updateMany.

- Filter:

"author._id": ObjectId("user1")— All posts where the author is John Doe - Update:

{ $set: { "author.name": "Johnny Doe" } }— Change the author name

Still not that complex.

3. Update comments they wrote:

db.posts.updateMany(

{ "comments.author._id": ObjectId("user1") },

{ $set: { "comments.$[c].author.name": "Johnny Doe" } },

{ arrayFilters: [{ "c.author._id": ObjectId("user1") }] }

)

Now we see some new things happening. Remember the 3rd argument of updateOne? It also applies here. It’s the options argument.

- Filter:

{ "comments.author._id": ObjectId("user1") }— All posts that have comments from John Doe - Update:

{ $set: { "comments.$[c].author.name": "Johnny Doe" } }— Update the author name of matching comments - Options:

{ arrayFilters: [{ "c.author._id": ObjectId("user1") }] }— Filter which comments to update

We see something new here: $[c]. Remember when we updated the text of a comment, we used the $ sign to get the first matching element? Well, $[c] updates all elements that match the filter.

So in the end, we do these 3 steps:

- Update user John Doe

- Update all posts that have comments from John Doe

- Within these posts, update only the comments that match the arrayFilter

Quite a piece of bread as we say in Dutch (quite a mouthful)! This is all well, but how do we handle this in our Symfony application? We always have to update everything when a user is updated.

There are 2 simple ways to handle this:

-

Creating a

UserServicewith anupdateUserfunction. Within this function, you execute all queries to update the users, post authors, and comment authors. The issue here is that we always have to make sure the service is used when updating a user. If anyone does$user->setName($newName);directly in the code, the data will be out of sync. -

Creating a Listener. This is the method I would prefer in this case, as we no longer need to be careful how we update the user. A simple example of such a listener:

#[AsDocumentListener(event: Events::postUpdate, document: User::class)]

public function postUpdate(User $user, LifecycleEventArgs $args): void

{

$dm = $args->getDocumentManager();

$changeSet = $dm->getUnitOfWork()->getDocumentChangeSet($user);

if (!isset($changeSet['name'])) {

return;

}

$collection = $dm->getDocumentCollection(Post::class);

$collection->updateMany(

['author._id' => new ObjectId($user->getId())],

['$set' => ['author.name' => $user->getName()]]

);

$collection->updateMany(

['comments.author._id' => new ObjectId($user->getId())],

['$set' => ['comments.$[c].author.name' => $user->getName()]],

['arrayFilters' => [['c.author._id' => new ObjectId($user->getId())]]]

);

}

What this does:

- Listen to

postUpdateof theUserclass - If the name didn’t change, we do nothing

- Update the authors of the Post collection

- Update the authors of the comments

A word of warning: We’re using the raw MongoDB collection here (

getDocumentCollection) instead of the Doctrine ODM query builder. This means you must use the database field names, not the PHP property names. In most cases these are the same, but if you’ve customized field mappings (e.g.,#[Field(name: 'user_name')]), you’ll need to use the database name.

Another caveat: These updates happen directly on the MongoDB collection, bypassing Doctrine’s Unit of Work. Any

PostorCommentdocuments currently managed by the DocumentManager will not reflect these changes until you refresh them from the database.

Query Comparison

| Page | MySQL Queries | MongoDB Queries |

|---|---|---|

| Homepage | 3 queries with 3 joins each (user, tag, post_tag pivot) | 2 queries, no joins |

| Post Detail Page | Query post, query author, query comments, query author for each unique comment author | 1 query |

| Search by Tag | Query tag, find post IDs (3 joins), fetch post details (3 joins), count total (3 joins) | 2 queries, no joins |

| Update Comment | UPDATE comments SET ... WHERE id = X |

Update the nested comment within the post document |

| Update User | UPDATE users SET ... WHERE id = X |

Update user, update post authors, update comment authors (3 queries) |

What about indexes? I didn’t dive into indexing strategy in this post, but it’s worth noting that MongoDB supports compound indexes, partial indexes, TTL indexes, and more. Proper indexing is crucial for performance at scale — maybe a topic for a follow-up post.

Conclusion

So, should you use MongoDB for your next Symfony project? As always, it depends.

I’m no expert, and I only made this demo to get a better understanding of MongoDB myself. So, I’ll leave that choice up to you.

What I found interesting:

- Reads got simpler — No more joins. One query gives you everything you need.

- Writes got more complex — Updating embedded data (like usernames) requires more thought and more queries.

- Schema design matters more upfront — Thinking about how the data is going to be used upfront becomes more important.

- Doctrine ODM works well — It felt familiar coming from ORM, though you occasionally need to drop down to raw MongoDB queries.

If you want to play around with it yourself, the code is available on GitHub.

Resources

Special thanks to everyone who helped me out by proofreading this post!